|

It’s not often that one gets to witness an actual schism unfold where it began. In this short video we get a quick tour of the Transfiguration Cathedral in Vinnytsia from Archdeacon Demetrios of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. This includes a visit to the undercroft which doubles as a bomb shelter, well as the meditation garden which has been used for centuries by monks and priests. Originally a Dominican monastery when founded in 1630, to say it has a fascinating history would be an understatement. The deacon begins with an explanation that this is the first church in Ukraine that transferred from the Moscow Patriarchate to the new Orthodox Church of Ukraine. A schism brought on by the war and is at the center of the conflict in many ways. Metropolitan Simeon was one of two bishops who came from the Moscow Patriarchate in 2018 to officially consecrate the new denomination as we see in a few photos of the historic signings creating the new church. The cathedral is the center of the Eparchy of Vinnytsia of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, with Metropolitan Simeon, its bishop. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transfiguration_Cathedral,_Vinnytsia The tour ended in the sanctuary which, at the time, was being used for the funeral of one of Vinnytsia’s heroes recently killed in battle. The fact that there are so many soldiers dying for their country necessitates the use of the cathedral for such occasions several times a week. Inside the Transfiguration Cathedral with Archdeacon Demetrios of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Vinnytsia - January 2024

0 Comments

The role of religion in Ukraine’s war against Russia’s invasion is increasingly evident as we hear about the treatment of Protestant churches and pastors in Ukrainian occupied territory. It is an ongoing story of Russian hypocrisy and terror. Just this week USA Today published an important article all those interested should read. It’s despicable to see how Russia’s rationale for the war has increasingly moved to the theological. Ridiculous claims of the need to “de-Nazify” Ukraine have evolved to the need for a full scale “de-Satanization” as they ramp up disinformation campaigns for their internal – and international – audiences, including the halls of the U.S. Congress. Nowhere is the fight more apparent than in Ukraine itself where the Orthodox Church schism between the Russian and Ukrainian churches started in earnest with Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and accelerated with Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. All of which leaves many of the faithful in Ukraine a bit unmoored as they try to navigate changing church calendars and competing claims and loyalties of clergy and congregations. It is a dynamic and evolving situation that I plan to delve into all the more in Beyond Bucha, the third film in the Trek to Bucha series.

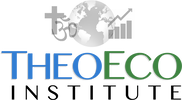

In this latest preview from the new film, we go into an Orthodox village church where Vinnytsia’s master blacksmith Roman created some of his best work, including the church’s steel door and candle case. We even get a tour of the inner sanctum behind the doors to the altar where we see the priest put away his robes. If you’ve never seen the inside of an Orthodox church they are wonders to behold with religious art from floor to ceiling. Everything is ornate and divinely inspired including the vestments/clothes, the bibles, the rugs, the ceilings, etc. Even iconoclasts have to marvel. A Blacksmith in Vinnytsia and his American Apprentice By Steve Richards “Thank God for technology” is a statement that means so much in Ukraine right now. From naval drones that are helping feed the world - and Ukraine’s economy - by decimating Russia’s navy, to a blacksmith in Vinnytsia. Ukraine is a high-tech country in so many ways, and their innovations on the battlefield, using the mish mash of NATO weapons they’ve received, are schooling the west on how vulnerable Russia’s army is. But to a blacksmith technology means something else altogether as we see in this latest short video. Here we are introduced to “The Forge” where they make “staples” to keep trenches intact. To a blacksmith and soldiers on the frontline trying to survive the winter, technology comes down to bending and putting points on small sections of rebar through sheer force. The technology? A press and a gas fire. A big improvement over old blacksmithing technology which came down to a hammer, an anvil, and a bellows like we see in old westerns. As we see in the video, staples are produced by the hundreds by two men in close quarters surrounded by scrap metal and other tools. Work that at one time would take nine brawny guys pounding all day for the same output. By the way, this is the first bit of video – first of three from the “Forge” – that will find its way into our new documentary Beyond Bucha - the third film in the Trek to Bucha series. My friend Ben Hoerber from Lake Worth Beach, FL is blacksmith Roman’s apprentice of sorts. Ben packed up his van last summer and shipped it to Belgium whereupon he drove it to Ukraine to help in any ways possible. He had begun studying Ukrainian more than a year before as he knew where he had to be. In his quest to do all that he could to help soldiers on the front lines, he found Roman and the blacksmith’s family whom we briefly see in the video as well.

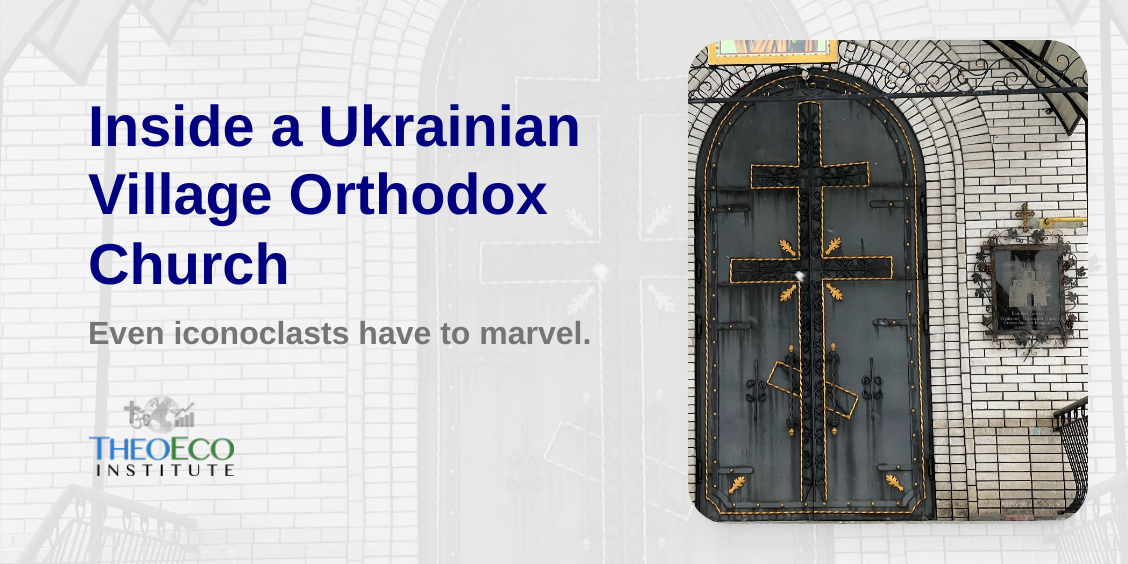

It was Ben who gave us the quote I began with. Turns out technology is relative but one thing’s for sure, Ukraine needs more of it – so much more. Which is one thing America has plenty of – and all Ukraine is asking for. High tech weapons and ammo for them. As President Zelensky is so famously remembered for: “I need ammunition, not a ride.” It is important to note that grass roots efforts throughout Ukraine is what is keeping Ukraine in the fight as much as anything else. Their Spirit is what makes them certain they will keep their independence. It is what has convinced the world that this David can take down their Goliath. To give an idea of how steadfast Ukrainians are: Roman has decided not to shave until they win. And a bottle of wine I brought as a gift to the host as we celebrated a village Christmas is still sitting on a shelf until victory. No matter how long it takes, the blacksmith and his family won’t be drinking. Nor will they be making anything but staples, furnaces, and other items for the front. As we’ll see in future videos these are artisans whose beautiful ironwork is seen throughout the area in local churches and elsewhere. But until the war is won they will be using their technology – and their labor - for the war effort. No more beautiful items until their work is done. All at no charge by the way. Like countless Ukrainians – and their supporters - inside and outside of Ukraine. Anyone who knows Ukraine knows that Ukrainians are a pretty conservative bunch by and large. Home and family are primary as is a Judeo-Christian based society dating back to St. Andrew in the 1st Century, where lore has it he preached the gospel from the banks of the Dnieper River. Almost a millennium later in 988 AD Prince Volodymyr baptized his entire Kievan Rus empire two centuries before Moscow was a speck on a map.

So why do Christian Nationalists in the Republican Party treat Ukrainians so non-Christianly? Ukraine is largely populated by folks they would likely have a great affinity with if they knew them a little better. We have so much in common as I have tried to document in my two films since the full-scale invasion we are remembering on February 24th. This includes the innate desire to raise their kids just like we do, with nice homes, schools, soccer fields, freedom - and peace. Moms in both countries also share an incessant fear that their children might not make it home from school in the afternoon. In Ukraine the fear is of missile/drone attacks. In the USA it’s the threat of a school shooting. Christian Nationalists have adopted Donald Trump as their political standard bearer and have imbued him with a kind of zeal for one that is heaven sent. Like a modern-day King David they simply see an imperfect figure whose crimes are akin to David sending Bathsheba’s husband Uriah to the front lines in a battle with the Ammonites. This conveniently allows them to avoid having to noodle too hard on the well documented sexual deviancy of their candidate. Or explain it to their congregations. Unfortunately for Ukrainians – and those concerned with the security of the free world - these same Christian Nationalists in the House of Representatives are calling the shots on Ukraine aid. This group reads like a who’s who of those opposing Ukraine, Israel, and other foreign aid. It includes Lauren Boebert, Mo Brooks, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Matt Gaetz, Louis Gohmert, the list goes on with more than half the House Republican caucus according to a 2023 report by the Public Religion Research Institute and the Brookings Institution. Talk about the tail wagging the proverbial tail. Only 1 in 10 Americans identify themselves with this Theo-political moniker – and yet these self-identified Christian Nationalists are the ones holding things up. Trump controls these votes, including Mike Johnson’s. This is an autocratic theocracy evolving before our eyes. Our country is losing its separation of church and state without much notice or outcry. Putin is seen by many Christian Nationalists as worthy of their praise because of his cynical support of the Russian Orthodox Church. But then, so did Stalin once the Russian Church had its independent voice squashed and became a tool for Russian communists. It’s voice is still silent, hence the immergence of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Trump sees it in his best interests to oppose Ukraine funding though it is not clear why. Ukraine has always been at the heart of his political “black box”. Going back to his first presidential campaign with the hiring of Paul Manafort, the Hunter Biden/Burisma accusations, the Mueller Report findings, his first impeachment, the list goes on. It seems apparent that these politically motivated Christian Nationalists are veering towards a time when their churches might also lose their independent voice. It’s already happened to a large degree. Trump and the Christian Nationalists in the image of Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church? It boils down to irreligious autocrats blessed by subservient and opportunistic church leaders. Go figure. David loved God. He wrote Psalms, fought battles, repented, and prayed for forgiveness. Can you imagine our former president doing any of these things?

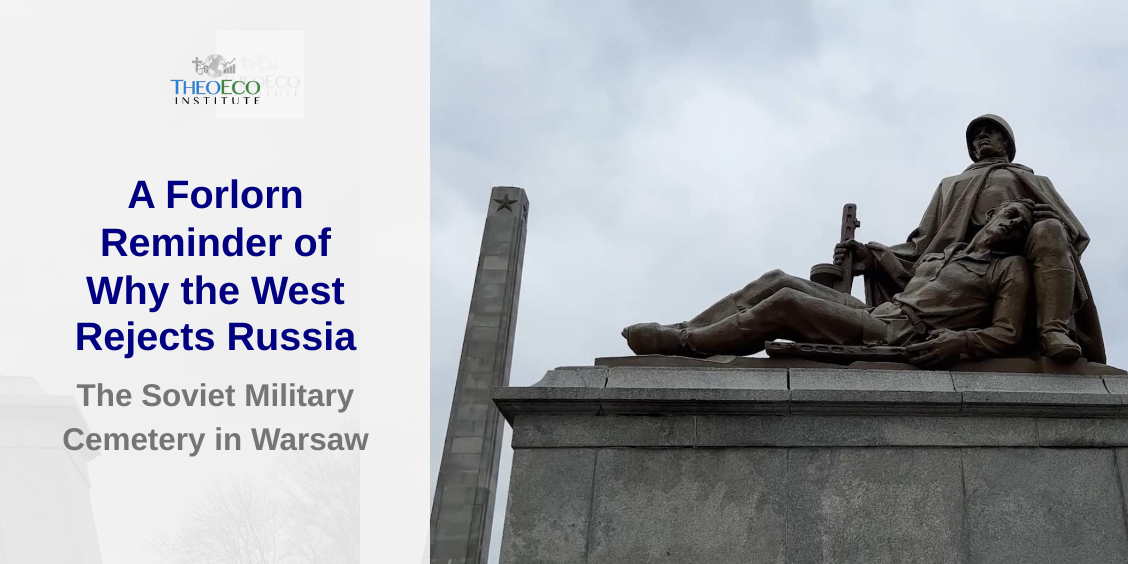

The Soviet Military Cemetery in Warsaw

BySteve Richards The day after Christmas I happened to be in Warsaw on my way to Ukraine and didn’t have much time. But I decided to visit a place that has haunted me since my first time there in March 2022. A place as cold and uncheery as I’ve ever witnessed. Soviet Realism is the manner of architecture and the monuments are reminders of Russia’s idealized history. It was meant to keep its former bloc in line including Poland and Ukraine. A place designed to mythologize the term: “Invincible Red Army”. Over two years Ukraine has certainly punctured that fairy tale. I’m talking about the Soviet Military Cemetery in Warsaw; final resting place to the ashes of 21,000 Soviet soldiers from the battle for Warsaw as the Red Army marched to Berlin. I went back to see if there was any more love for the place at Christmas, which might also reflect a bit of love for Russia. It was no different. Not a single wreath. No poinsettias. Not a single string of lights. Just a forlorn miserable place with an occasional straggler taking a shortcut home. I suppose the twilight added to the miserableness; it made the towering red starred obelisk doubly dark. This to me seems like a pretty good metaphor for how the former Soviet satellites – like Poland - are reacting to Russia’s war in Ukraine. They get what’s at stake.

A short video of the cemetery in March 2022. It looked identical at Christmas 2023.

Germany’s blitzkrieg through Poland in 1939 was the real beginning of WWII. It included a devastating siege and bombing of Warsaw – with the acquiescence of Stalin and his infamously dirty deal with Hitler to partition Poland with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Russia invaded from the east in September 1939, two weeks after Nazi Germany invaded from the west.

Which gets to the heart of why there is no love for the Russians…or their graveyard. Because the only reason the Red Army had to retake Warsaw in the first place was because Stalin gave it away. Of course, Hitler invaded Russia less than two years later after marching through the rest of Poland. Let’s face it, when you make deals with autocrats, dictators, and tyrants, be ready for them to turn on you. Something we need to be cognizant of in this election cycle. Zelensky recognizes this “Stalinesque” core in Putin. So does the West. None more so than the former Warsaw Pact countries that the Iron Curtain fell on at the end of the war giving rise to NATO and the Cold War. Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary, and Poland are all former Soviet bloc countries that regained their independence with the fall of the Soviet Union some 30 plus years ago. None were forced to join. All of them have citizenries that wanted to be part of a free Europe, like Ukraine does. All of them had the choice to stick with Russia; none did. Poland is at the heart of NATO’s shield against Putin and Russia’s expansionist nightmare. They have a vibrant economy, a welcoming people, and are a primary conduit for arms and ammunition to Ukraine. They are a shining example right next door for Ukrainians and have much shared history over a millennium, not always on the same side. They are making sacrifices without whom Ukraine would have little chance to win. The Poles see it as an existential cause since a defeated Ukraine would mean a reconstituting, belligerent Soviet Union next door with a new Stalin in the form of Putin. This lays bare the possibility of millions more dead in Poland and Ukraine. What would prevent it?

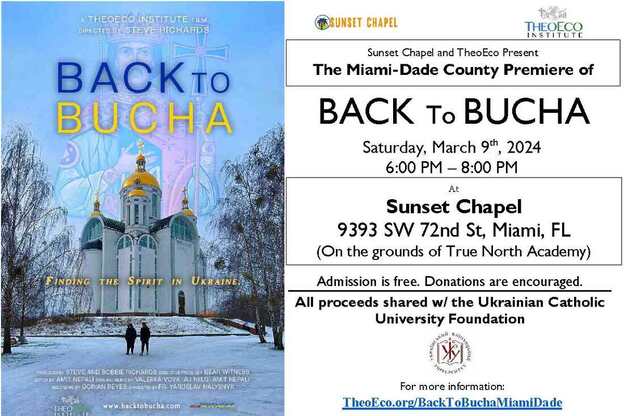

Ukraine’s Sprit On Full Display March 9thI am very pleased to announce the premiere screening of Back to Bucha in my hometown of Kendall, FL, just southwest of Miami proper. Technically, it is part of unincorporated Miami-Dade County, so we are calling this the Miami-Dade premiere; but I digress… The screening takes place on Saturday, March 9th beginning at 6:00 PM. With Q&A and a potential surprise or two, the entire event will be a two-hour affair. It takes place at:

Sunset Chapel

9393 SW 72nd St, Miami, FL (On the grounds of True North Academy)

This is a donation driven event and all proceeds will be shared with the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) in Lviv through a donation to its USA based foundation.

This is our first screening/fundraiser for the university and is long overdue. It was the first place I went on my original trip to Ukraine when I arrived unannounced at the reception desk on March 31, 2022. I told the receptionist that I was there at the suggestion of Fr. Yaroslav of Christ the King Ukrainian Catholic Church (UCC) in Boston, who had told me that if I made it to Lviv I should stop in. As the Spirit would have it, the next day I was shooting interviews and staying at the UCU Inn where I experienced my first air raid sirens and visits to bomb shelters. Several days later my plans had been turned upside down with the retreat of the Russians from Bucha and the other suburbs of Kyiv, allowing me to go there. The rest, as they say, is history. Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) in Lviv (theoeco.org) UCU is a renowned educational institution in Ukraine known to be free of corruption and tops academically. In other words, you can’t buy your way in. It is a beacon of values we can all recognize, and my time there made me understand Ukrainians are just like us. Especially the students and teachers. Following is a 12-minute video shot I shot there in 2022:

Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, Ukraine - April 1, 2022

Even though Back to Bucha is a secular film one can’t help but recognize the Spirit imbued within it where so many of the interviewees actually mention their beliefs, which to me sounds like I’m listening to folks I might meet in Anywhere, USA. Especially moms who have moved back so they can raise their children, in their own homes, in their own country.

People like those at Sunset Chapel. When I first stopped in to see my good friend Jovy play with the band on a Sunday before Covid I saw it was as welcoming a place as I’ve ever been on a Sunday. Pastor Russ immediately affected me in the manner all great preachers do. Plus the sanctuary was filled with flags from around the world, including Ukraine’s, and when I saw the big screen I knew I had to ask. It will be a great place to watch the film.

To register go to the event page at:

https://www.TheoEco.org/BackToBuchaMiamiDade

My first Ukrainian Orthodox Christmas Included Gifts, Feasts, Churches, and Angels Made From Shell Casings

Yes, I know; you thought Christmas was over two weeks ago. And they were certainly celebrating the occasion around here then. But Orthodox Christmas was yesterday, January 7th and the celebration goes on. The trees are still up, and the store decorations are still out. Back to Bucha’s Ukrainian Premiere on Friday included a ceremonial check presentation from the October 1st screening in Boston at the St. Andrew’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The next day had me using the funds to personally buy a new video camera and powered speaker for the local children’s center which replaced equipment pilfered by Russian soldiers during the occupation.

Then, I was on my way to Vinnytsia with my friend Ben to a small village outside of the city and a Christmas Eve feast with a blacksmith that Ben is working with, and his family. They also celebrated on the 25th with a more traditional western X-Mas when they all watched Home Alone together, a holiday favorite here too!

I’m keeping the names and exact locations a bit vague just in case anyone confuses their humanitarian work with something more offensive in nature. We had a Christmas Eve feast that included hot borsht and an assortment of meatless dishes.

Then after some conversation with Ben providing translations - and a mammoth log thrown in the furnace – it was time for bed. The next morning, we had a breakfast of nothing but meat dishes it seemed. 5761

Then outside to the “forge” a few steps away to make “staples” and “furnaces” for the front lines. The staples are used to keep logs together inside trenches and the small furnaces they make out of scrap metal are used to keep soldiers warm. A difficult task when the thermometer will drop to -3F (-21C) tonight where I am in Lviv. This kind of volunteering is happening all over Ukraine to support the war effort in a myriad of ways. The blacksmith and Ben receive no remuneration for this work.

Before the blacksmith started making things for the soldiers, he made artisan craftsman work including churches nearby. He still creates artistic works like angel candle holders out of 30mm spent artillery casings. Before the war he also made metalwork for local Orthodox churches like those we visited on our way into the city.

It was here that we met three village ladies caroling from house to house in the morning hours. I had heard to look out for these caroling groups in Ukraine but figured with the bombings of Kyiv I would be out of luck. These ladies definitely made my trip!

Then back into Ben’s van (he brought it with him from the USA when he came five months ago) on snowy streets to the Transfiguration Cathedral in town.

We then got a tour of the church and also witnessed the funeral for a Ukrainian soldier there. They average about one per day we were told. After a promise to come back I was promised a proper interview with the archdeacon host – including a discussion of their rather recent break from the Moscow Patriarchate and a Metropolitan still under house arrest. 5822 5834

All this in less than 24 hours. Then we piled back into Ben’s van and off to the train station for the next leg of my journey home.

Livestreaming From Bucha This Friday January 5th at 12:00 Noon ESTIt seems like only yesterday when we first walked into a blown-out Jul’s coffee shop just days after the Russian retreat from Bucha. No electricity, no water, no windows, just a few shell-shocked workers sweeping up broken glass in the cold trying to get to the point when they could offer free coffee to workers and neighbors starting to rebuild.

It is a fitting place to hold the Ukraine premiere of Back to Bucha as it holds such a prominent place in the film, including an interview with Julia, the shop’s owner who has rebuilt the place with the help of so many. The picture we are using to promote the event is of she and her daughter from a year ago when visiting the renovated shop, newly rechristened as Jul’s Coffee and Peace (https://www.julscoffee.com/en). Taken all together they display the best of Ukraine and its Spirit. Because while Bucha is remembered for the atrocities committed there (Bucha massacre - Wikipedia) it is also the site of Ukraine’s first victory of the war as they forced the Russians into a humiliating retreat a month later; an example of what Ukrainians are capable of when provided state-of-the-art weapons like Javelin missiles. Bear Witness, the film's Executive Producer, is sponsoring the free event which doubles as a fundraiser. Which is where our supporters and friends can make a difference. We will be livestreaming the hour-long screening beginning at 12 noon east coast time (7:00 PM Bucha time). Additional screenings will also be held at Jul’s for the citizens of Bucha on Saturday and Sunday. After the screening director Steve Richards will be joined by Julia and others from the film for a Q&A session. Ivan Rusyn from the Ukrainian Evangelical Theological Seminary will also be in attendance and join in from Bucha. 50% of the event’s net proceeds will go to providing free bags of Jul’s coffee to soldiers on the front lines. Here's a video of a soldier making a cup of Jul’s milled coffee at the front:

She has personally sent more than 500 bags so far.

To attend this event virtually go to: https://watch.showandtell.film/watch/backtobucha. See you there!

By Steve Richards

Given that I’ve never before celebrated New Year’s in Kyiv I’m not sure what I should have expected. In the USA New Year’s Eve is generally thought of as the end of the Holiday Season which begins in late November with Thanksgiving then Christmas on December 25th, culminating with a big night of partying on New Year’s Eve. New Year’s Day is set aside for recovery. Resolutions are made, often not to drink so much for the next few weeks at least. Ukraine’s holiday calendar is in flux due to the war. Used to be most of the country celebrated Christmas on January 7th according to the Orthodox church calendar. But patriotic fervor has caused the country to rethink that day because it is celebrated in Russia. December 25th has become the day for most here to coincide with European calendars. Additionally, for many the holidays really begin on St. Nicholas Day which is celebrated on December 19th and includes church services and gifts by the pillow for children. New Year’s Eve here for most is a time with family and friends who celebrate the day together. Maybe a swim in a heated pool/spa, a nap, a feast with all kinds of traditional foods, gifts and a midnight celebration which appears to center around the kids. Or so I surmise. Again, this is my first time. Apparently though I still have another week to see what happens as I’m sure many will celebrate Christmas on the 7th. My own quest for a New Year’s Eve experience I might recognize found me at a celebration at Kyiv’s Ukraine Hotel where I am staying. It promised a Gala Dinner and Festive Breakfast. With a $40 price tag how could I go wrong? Well the dinner was amazing and provided eight plus courses – I believe dessert was the ninth, but I lost track. A $15 bottle of champagne was extra. But Kyiv is not celebrating anything too heartily at present. There was no band or dancing and a rather sparse crowd of 20 or so in the ballroom. The mirror ball was kept in the dark. The massive missile strike throughout Ukraine on Friday probably had something to do with the somber mood in Kyiv. Air-raid sirens and alerts have been frequent, and folks have been warned not to set off fireworks.

All in all though I felt like I must have found the biggest celebration in town. It felt festive in a subdued way in the largely empty ball room, especially when a party of 10 or so young ladies showed up dressed to kill. I used most of the time keeping track of the throttling my Dolphins were receiving at the hands of the Ravens on the ESPN app. The staff tried their best and made it all work.

After I finished my dinner I decided to take a walk down to Match Restaurant just to see if any additional celebrating could be discerned. The hotel is in the center of town overlooking Independence Square. If there was anything going on in Kyiv it would likely be around here. Nothing. Zilch. Nada. It was a ghost town out there aside from a few stragglers and a group of youngsters hooting a bit on their way home to beat the midnight curfew, a few well-armed police officers standing watch. The food and coffee stalls normally open were closed up. The streets were empty. Fireworks were nonexistent and Match was closed.

So back to the hotel for me just in time to catch midnight merry making by the “crowd” in the ballroom which included the singing of the national anthem and a small dog looking for some petting, which I happily provided.

I’m thinking the crowd kept it going for a while, but I decided I could avoid a hangover if I just went to bed. Getting old I guess.

The scene at the Ukraine Hotel at midnight on New Year's Eve 2023-2024 in Kyiv.

The scene at the Ukraine Hotel at midnight on New Year's Eve 2023-2024 in Kyiv.

Witnessing Kyiv Under Attack This Morning

By Steve Richards

As I visit Ukraine during the holidays and premiere my new documentary for Bucha next Friday I thought I was just going to send out an update today of a post from earlier this year about how nice Kyiv was. All about how pleasant it is here; how everything is open and how nicely people seem to be getting along. Going to work, shopping, eating out. There's solid power, cell service, and wi-fi. Most of all it was about how Kyiv had obviously adjusted to this war. All of which is true. (Hello from Kyiv! Wish You Were Here) If anything, I didn’t realize just how well. Missile strikes woke up this city after a night filled with air raid sirens, which I largely slept through. I personally witnessed two explosions clearly visible from my room about a mile or so from the hotel. It totally freaked me out and it didn’t take me long to find the bomb shelter after ignoring so many air raid sirens in the past. This is my third visit since March 2022 and the first explosion I have witnessed personally. The first blast shortly before 8 AM got me out of my seat and to the window where I could see smoke rising from behind St. Sophia’s Cathedral a kilometer away. At that moment I collected myself enough to begin shooting footage from my 11th floor window overlooking Independence Square. The second explosion rocked the city just before I hit the record button fireball and all. If you watch the video clip you can still hear the explosion echoing through the city as I just missed filming the blast. The smoke plumes are clearly visible and in more than one spot. Fortunately injuries were few. Apparently, there was a “massive missile strike” this morning on targets all over Ukraine. Also reported is that all the missiles targeting Kyiv were intercepted. What I witnessed was debris falling to the ground. It would appear that unexploded war heads count as “debris”. It is impossible for Americans to relate to such things though we are used to things that would make Ukrainians shudder like mass shootings. The idea of a missile strike on the USA by Russia – or any other country - is unthinkable, except to nuclear war planners that started preparing for Russian ICBM strikes in the 1950’s. Those plans are still in effect as Russian warheads are still pointed at us. But what is most intriguing for a guy like me is how nonchalant Kyiv’s citizens are to such attacks. They are so used to it. Nothing closed down though the hotel staff did go to the bomb shelter for 30 minutes or so. But when it was over they all got back to work. The net effect on my day? A breakfast appointment got pushed back an hour or so due to traffic tie ups as did my appointment with the barber. By the time I left my hotel at lunchtime the smoke plumes were gone. That’s it. Like nothing happened. People about their business. As Julia said in Back to Bucha reflecting the spirit of all Ukrainians living through this war: “You really do get used to anything.” |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

TheoEco Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Contributions to TheoEco in the United States are tax exempt to the extent provided by law.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed